Amnesia, nostalgia, healing: Spain grapples with Franco legacy

Half a century has passed since Francisco Franco's dictatorship ended with his death, but some today valorise his rule.

Granada, Spain - This summer, Marina Roldan, a lawyer from Granada in southern Spain, finally got the phone call her family had waited decades for.

The body of Fermin Roldan Garcia, her grandfather, who was one of tens of thousands of people killed by General Francisco Franco’s death squads in the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War, had finally been located and identified.

His remains were found in a ravine in the village of Viznar, a few kilometres outside Granada.

“My brother Juan called me. He’d been the family contact with the archaeological team carrying out the excavation,” Roldan told Al Jazeera. "When Juan told me my grandfather had been found, my first thoughts were for my [late] father."

Her father, Jose Antonio Roldan Diaz, was just 10 months old when his father was killed at the age of 41.

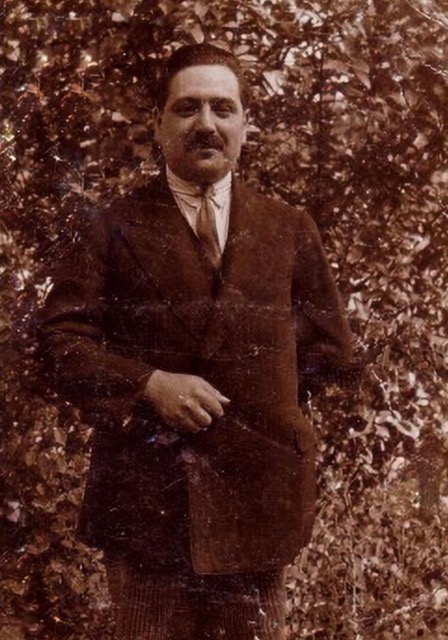

Roldan Garcia was a tax inspector, a trade unionist and a member of the Socialist Party who stood unsuccessfully for parliament in the February 1936 elections in Granada.

As Marina remembers them, her voice falters with the emotion of it all. The noise of passing trams echoes through an open window of her office.

“I thought of [my father] and I thought of my late uncles, who would have liked to have heard the news, and my grandmother too. ... I think they all deserved their husband, their father, to be found.”

On Thursday, Spain marks 50 years since the end of Franco's dictatorship - four decades that ended with his death on November 20, 1975.

'They talk like they are really in favour of the dictatorship'

Young people in Spain, glued to their screens, are developing a nostalgia for a dictatorship they did not live under.

After Spain's first fully fledged modern democracy and Second Republic began in 1931 despite ferocious opposition from hardline conservatives, Franco began a right-wing military rebellion on July 18, 1936, to put an end to its political and social reforms.

Despite backing from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, his uprising encountered greater resistance than expected from a makeshift pro-Republican coalition of left-wing trade unionists, political parties, some parts of the armed forces and pro-democracy activists, leading to a full-scale, brutal Civil War lasting three years.

The republic finally surrendered on April 2, 1939, leading to his regime.

Since the earliest days of the war, a brutal repression of suspected civilian rivals and their families had begun in the Franco-controlled areas of Spain. It was designed to silence and intimidate any possible opposition.

The number of victims who were summarily executed is estimated at 130,000 to 200,000.

In the half-century since Franco's demise, exhumations have been slow and beset by logistical, financial and legal challenges. There are an estimated 6,000 unmarked mass graves dotted around the country, including everywhere from wells and woodlands to gardens, cemeteries and remote hillsides.

But as Spain remembers the era's victims and analyses exhumation efforts, it is grappling with the steady recent rise of a far-right party, Vox, and nostalgia for the ideals of the dictatorship among young people who did not endure it.

A recent CIS poll suggested that 20 percent of those aged 18 to 24 believed the dictatorship was "good" or "very good".

According to secondary schoolteachers, social media is driving pro-Franco support among teenagers.

“They talk like they are really in favour of the dictatorship and of obligatory military service as well,” Jose Garcia Vico, a secondary school economics teacher in Andalusia, told Al Jazeera.

“The majority of the teachers I know are very worried because even if we’ve explained the difference between dictatorship and democracy, the students are so overrun with content from TikTok and they’re so p***** off with the world in general, they don’t know what they want.”

“The content they get from the hard-right parties on social media aimed at adolescents is considerable, and it has a lot of effect on how they relate to each other.”

While emphasising “not everybody in the class” is attracted to the far right, Garcia Vico points to a parallel sharp rise in Islamophobic and anti-transgender comments.

“Above all, it’s the boys who feel superior to the rest. But it’s a problem which involves some of the parents as well. A couple of years ago, some parents told me that it was OK that their child had interrupted me by shouting, 'Viva Franco!’ ['Long Live Franco!'] because that was freedom of expression.”

Hundreds of kilometres north in the capital, Madrid, Sebastian Reyes Turner, a 27-year-old teacher, said he has also noticed the impact of hard-right social media influencers.

“In schools, people only see Franco’s dictatorship as one of several topics to mindlessly memorise to pass a history exam they don’t really care about to begin with.

“On the other hand, details are cherry-picked by the far right to make them think it was a better time in which they didn’t face problems like they do today - like how hard it is to find jobs even if they’ve been studying well into their 20s or the housing crisis.”

'Mythification' of the Franco years

Experts draw parallels with other European nations where the far right appeals to those attracted to the idealism of a 'simpler past'.

Political analysts said Vox's attitude to the Franco dictatorship shows underlying sympathies for the former regime without any sense of embarrassment.

Last year, Vox lawmaker Manuel Mariscal boasted in parliament that “thanks to social media, many young people are discovering that the post-Civil War era in Spain was not some dark time but a period of progress and reconciliation towards national unity.”

“There is a type of mythification of the Franco years that works well on social media, and it has a big impact on young men in particular. They are told there were no problems in that era because there was no radical feminism and no migrants out there on the streets,” said Oriol Bartomeus, a research professor at the Institute of Political and Social Science at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and author of a book on generational change in Spain, El peso del tiempo, or The Weight of Time.

“You can hear the same kinds of claims now in the United Kingdom, the USA, Germany and Italy - that a return to a simpler past where the white men were in charge of the ship is possible.”

However, none of these countries had a dictatorship as recently as Spain, where Vox commands nearly 20 percent of the vote and is steadily rising in polls.

Bartomeus noted a generational shift in the right-wing electorate from the traditional Partido Popular (PP) - “it’s increasingly becoming a party for old people” - towards Vox.

On the other side of the political spectrum, left-leaning voters have a critical stance towards the regime.

After democracy returned, there was a "tendency to keep looking forward, forgetting the past and concentrating on integration into Europe - a kind of collective amnesia”, he said

“It’s only when the generation of Spanish baby boomers, born between 1960 and 1965, starts to impact politically that there’s a clear shift in the Socialist Party to overcome that amnesia. They are the generation who argue the dictatorship can’t be ignored. They’re the ones who say, 'Let’s open up the roadside graves.'

“It started with [Socialist] President Rodriguez Zapatero and his law of 'historic memory' in 2007” - Spain’s first law that fully addressed the Franco regime and began an ongoing process of removing the hundreds of dictatorship-era symbols and architecture from its streets and squares.

“They’re the people that open up the can of worms. And that in turn has created the reaction you’re getting from the neo-Francoists of today.”

The politics of condemnation

After the dictatorship ended, some parties took a vow of silence instead of vociferously rejecting Francoism.

Since Franco died, Spain has witnessed massive social progress.

To take women’s rights as an example, in 1975, the last year of the regime, married women had equivalent legal status to the mentally ill and illiterate and were banned from signing contracts. They could not travel, work or open a bank account without their husbands' permission.

By 1981, there was a divorce law. By 1985, abortion was decriminalised, and by 2005, same sex marriage was legalised.

But at the same time as Spain moved away from the dictatorship, the PP was one of the few mainstream parties in Europe that failed to categorically condemn the regime.

“The problem is that unlike Germany's or Italy’s 20th century dictatorships, Franco’s government doesn’t get overthrown. It simply ends," Bartomeus said.

“That absence of a formal rejection permits a kind of sociological Francoism to remain in place, and that’s why there can still be a lot of people inside the PP who, even today, are still pro-Franco.”

Spain is only now taking concrete action to ban the Francisco Franco National Foundation, founded in 1976 to, as its website puts it, “promote the study of the life, legacy and work in its human, political and military aspects” of the man who “governed the fate of Spain between 1936 and 1977”.

Meanwhile, Vox opposes exhumations. The party is also furious that Franco himself was exhumed from his own specially built mausoleum outside Madrid, previously known as the Valley of the Fallen, and given a more discreet burial in 2019.

This month, architectural plans were approved for Franco’s former tomb to be remodelled as a politically neutral Civil War heritage museum.

Although excavations like the one in Viznar are proceeding at an unprecedented pace, archaeologists are concerned that at some point, a new right-wing government would cut off financing and threaten projects that reckon with the past.

“It has already happened once,” said Francisco Carrion, an archaeology professor at the University of Granada who has overseen the regional and state-backed Viznar investigation and exhumations for the past five years.

“The previous PP government with Mariano Rajoy didn’t suspend the 2007 law of historic memory. But during his time in power, he did cut off absolutely all funding for the exhumations. They cut it right down to nothing.”

Likening the massacres and executions in Franco’s era to the current Israeli attacks on the Palestinian civilian population in Gaza and the occupied West Bank, he said among those killed - like Marina Roldan’s grandfather - were trade unionists, teachers, seamstresses and artists.

In Viznar, his team have even discovered the executed remains of a child aged 11 to 14.

'A complicated process emotionally'

Excavations bring pain, a sense of closure and healing.

A few metres away from the exhumation site, in the converted mill that acts as the headquarters for Carrion's investigation, his colleague Jose Francisco Munoz Molina, a forensic anthropologist, is working on two of the 166 skeletons that have been exhumed so far.

One has traces of a bullet wound in the arm, he explained, and the other was shot in the head.

“It’s a complicated process emotionally. It can affect you a lot,” Munoz Molina said. “You’re dealing with people who were very close to our own ages, who were very young in many cases. It’s hard to understand how this all happened.

“My own great-grandparents were executed against the walls of the city cemetery in Granada during the Civil War."

About 3,400 people in the early part of the Civil War were reportedly executed against Granada's cemetery walls.

"I’m doing something for families who have been looking for them for such a long time, and it’s going to help heal them, so it’s healing me a little bit as well.”

The latest series of excavations this autumn produced 12 more bodies, Carrion said.

Although it’s much too early to say, he said cautiously, they hope to have found evidence of one of the bigger mass executions of October 1936, including of the rector of Granada University, Salvador Vila.

As for the still undiscovered remains of Federico Garcia Lorca, Spain’s most famous modern-day poet, Carrion is less hopeful. There are several theories as to where exactly in the hills of Granada he could have been killed.

“It’s true that Garcia Lorca is dead but also that he lives on too, in his books across the world, in so many different translations. On a human level and regardless of his poetic contribution, the 166 other people we’ve so far exhumed are just as important too.”

The moment of handing over remains to relatives “is the best part of our work. They are very emotive ceremonies. It’s almost magical because we’ve given them closure after so many years,” Carrion said.

He recalled the case of two daughters, aged 92 and 93, who were both suffering from Alzheimer’s disease but who were somehow able to have brief moments of mental clarity when the box containing the remains of their relative was handed over.

“When they held the box, they knew what was happening. It makes you cry. You’d have to be made of stone not to be affected.”

In the case of Marina Roldan, her only impression of her grandfather for years was from the portrait in the bedroom she shared with her grandmother - “one of those old ones where it looks as if whatever you do, his eyes are following you, so I always had the impression that if I did something wrong, in my head he’d tell me off”, she said with a laugh.

“Now there’s a real story, a real background. But I don’t have the sensation of an open wound being closed, more a kind of calm because I feel that my dad would be happy and that he too is resting now.”